Thought Leadership

Market observation

Good morning, Mr. President

"Today we're standing up for the American

worker and finally putting America first."

It’s not beyond the realm of impossibility that

Donald Trump’s charm may have run thin, and

that he may just be rubbing you up the wrong

way. So, before judging too quickly, let’s do a

thought experiment ...

Welcome to your new job, POTUS. Having won

the popular vote, as the newly elected President

of the United States and its Commander-in-Chief,

you have just sworn to “preserve, protect, and

defend the Constitution of the United States.” If

you knowingly act against US interests, you may

be impeached. So be careful. Your inauguration –

the greatest ever - was streamed across all major

digital platforms. We saw you fighting that hat in

an attempt at a kiss after taking the oath! There is

no place to hide.

Time to get down to

work. This is what faces

you today.

Let’s start with the economy.

All is not well.

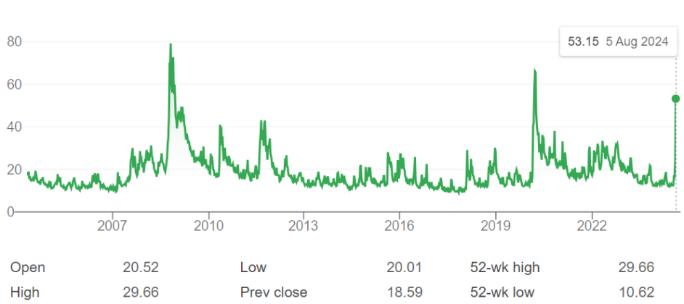

The end of American

exceptionalism, a period

that created enormous wealth – driven by

technological advances that enabled people and

capital to become far more productive, has lost

momentum. In truth, the US has turned from a

productive economy to a consumer economy. As a

result, it has experienced a surge in debt which

has been required to sustain comfortable

lifestyles. Fortunately, the reserve currency status

bestowed on the US has allowed increased

borrowing beyond limits available to mere

mortals. As is typical, the availability of leverage

has culminated in the formation of financial

bubbles. This “everything bubble” post the

enormous 2020 stimulus has manifested itself in

equities, crypto, digital art, luxury goods and even

Pokémon playing cards. It has also seen enormous

wealth gaps between the haves and have-nots ...

with the political consequences this holds,

including your own (well deserved) and

incontestably free and fair election victory.

No good deed goes unpunished. Having provided

USD 5 trillion in relief aid during Covid (the CARES

Act, the largest in U.S.

history, provided USD2,2

trillion directly to

individuals), the trailing

period of revenge spending

is unfortunately coming to

an end. The consumer is

increasingly tapped out and

fast losing steam. All that is

left is the debt; USD36

trillion and counting. Of this, about USD8,5 trillion

is owed to mischievous foreign investors.

“We’re going to stop the manipulation, the

cheating, and the theft of intellectual property.

It’s going to be better for the world, better for

our country, and better for China.”

Over the long run, a country’s wealth is a function

of how much it can produce (a measure of its

productivity). And wealth is power. The creation

of too much money and credit leads to a process

of devaluation. When you borrow excessively, it

creates fragility. You become reliant on foreign

lenders. If they lose confidence and look to sell

your debt, your currency comes under pressure.

You start to lose power. If coupled with an

economic downturn, the risk of internal conflicts

increases, and politics becomes more radicalised.

Across the Pond, your latest bestie and special

relationship, Keir Starmer, has reacted to the

growing divide by doing the tough popular thing

and taxing the rich ... and then waiving as they

board one-way flights to warmer destinations. Uh

oh. We don’t want to make that mistake and tax

ourselves.

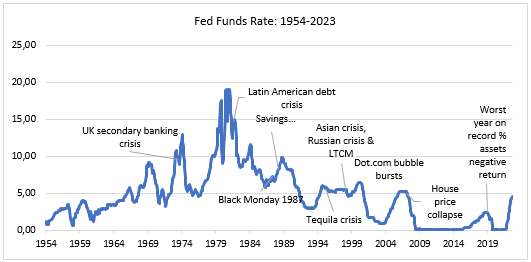

What happens when your debts are too large, and

you hit an economic downturn? You can print

money, or you can default on your debt. If you

print money – which countries always choose over

default – you increase inflation. And consumers

hate inflation – a tax on their wealth – and which

for the moment is proving stubborn and just

won’t fall back into line.

At these times, Governments increasingly struggle

to fund themselves. What can be done? For one

thing, get your house and spending in order.

Queue DOGE and enter (and exit) current bestie,

Elon Musk, whose kitchen-appliance approach will

(hopefully) cut USD2 trillion off the USD7 trillion

Federal budget and eliminate ideologically driven

initiatives (such as diversity, equity, and inclusion).

"Our allies have taken advantage of us more so

than our enemies."

Concurrently, with power waning you need to

withdraw from the global stage as military

strength requires enormous spending; 13% of the

Federal Budget. As an aside, your European free-

riders friends spend just 1.3% of their budget on

this. And they have an angry bear living in the

woods next door. Unfortunately, departing from

the scene creates vacuums that are quickly filled

by rising powers and / or desperate powers

looking to re-assert themselves. But you need to

choose your battles – you can’t fight on every

front – and sacrifices will need to be made. Sorry

Ukraine. Let’s talk about Taiwan later, as the USS

Carl Vinson is steaming to the Middle East.

“China is an economic enemy. They are the

enemy of the United States, and they’re taking

advantage of us.”

Turns out that China has not played by the rules

even after you invited them into the World Trade

Organization. Despite promises, they have not

upheld intellectual property rights in compliance

with international trade agreements – leading to

intellectual property theft, cyber-espionage

(continued hacking and stealing US data),

counterfeiting and forced technology transfers –

pressurising foreign companies to share their

proprietary technology, trade secrets, or

intellectual property with Chinese firms or the

government as a condition for market access. And

now they seem to be standing on their own feet,

introducing AI across a range of initiatives

spanning Military, EV’s and healthcare. Sceptical?

Just ask Deepseek!

OK, that’s enough for one day! I can already see

you reaching for that thick black Sharpie marker ...

time to level the playing fields, act in America’s

self-interest, and sign those tariffs into law.

(P.S. You can’t take credit ... all the above quotes

belong to Donald J Trump – the actual POTUS.)

Navigating wealth through the crisis

Let’s get serious. This is a crisis. The scale of the

tariffs introduced are stunning in their scale and

reach. This brings the period of globalisation and

free trade to an end.

Tariffs introduce significant costs that are

important to understand. Some of those costs are

direct and obvious, while others stem from

uncertainty – which will impact return on capital

and growth globally, which includes the U.S.

themselves. Tariffs introduce currency volatility,

particularly as countries retaliate. Profit margins

will be squeezed – especially for those doing

business in the U.S. and those with frail balance

sheets may not be able to survive. Increased

bankruptcy risk, at a time of tight credit spreads

means that U.S. high yield corporate credit looks

to be a particularly bad trade. It seems obvious

that tariffs are also inherently inflationary.

Understanding the consequences, it is our

absolute responsibility to protect your assets

through this period.

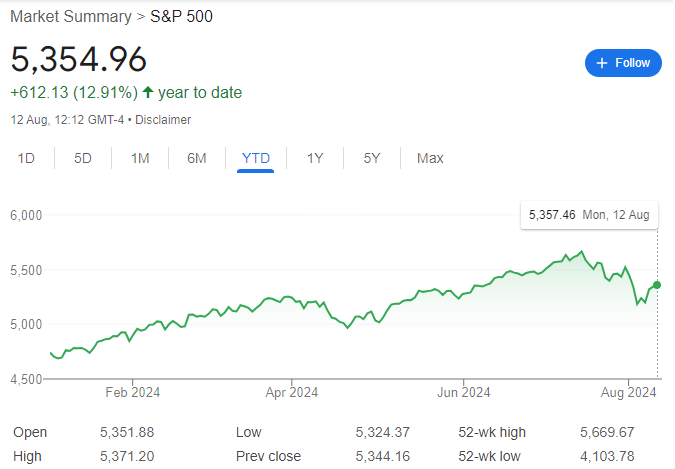

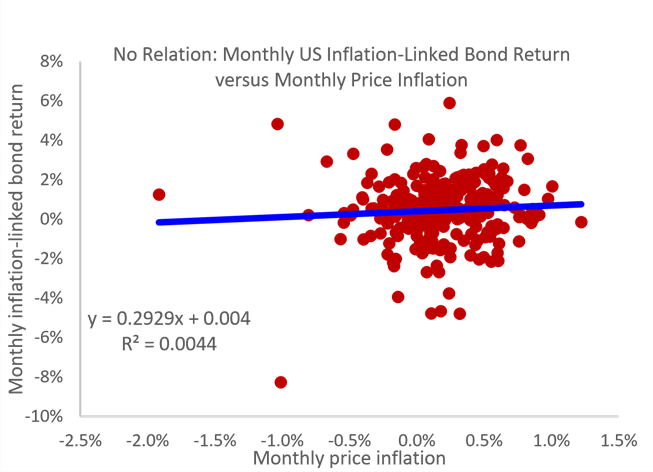

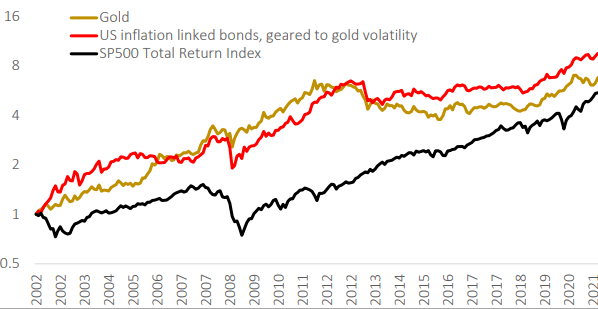

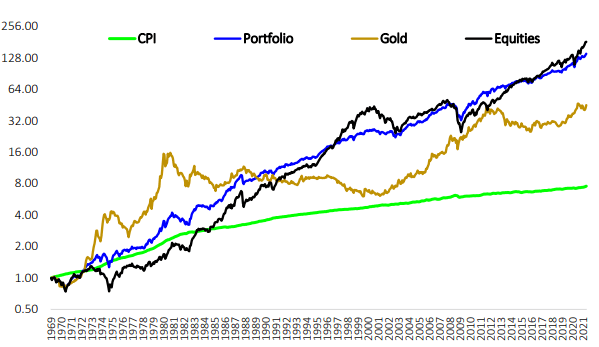

As you will be aware from our previous

correspondence (please refer back to our 2024

Investor Letter), our view has been that inflation

expectations were unrealistic, that equity

valuations in the US, particularly the Magnificent

7, would prove problematic to justify given the

over optimistic view of AI driven productivity

gains, and the continued reliance on

unsustainable levels of debt to stimulate markets.

All combined, these commonly held assumptions

had created an unstable foundation – and one

prone to structural instability.

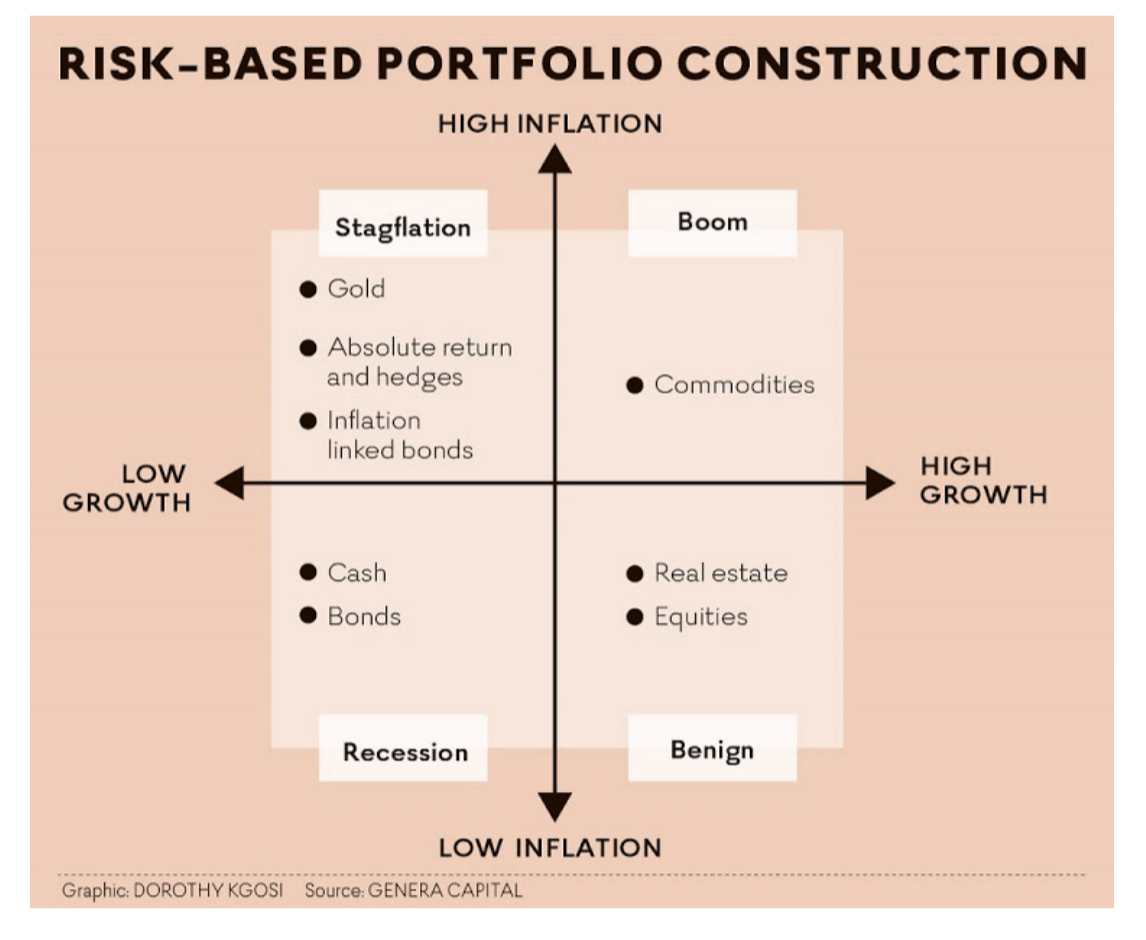

We have been deeply concerned about the

increasing risk of stubborn inflation and a looming

recession. The consequences for growth assets –

and US equity in particular – are significant. And

we have long positioned our core balanced

portfolios looking ahead to these risks playing out.

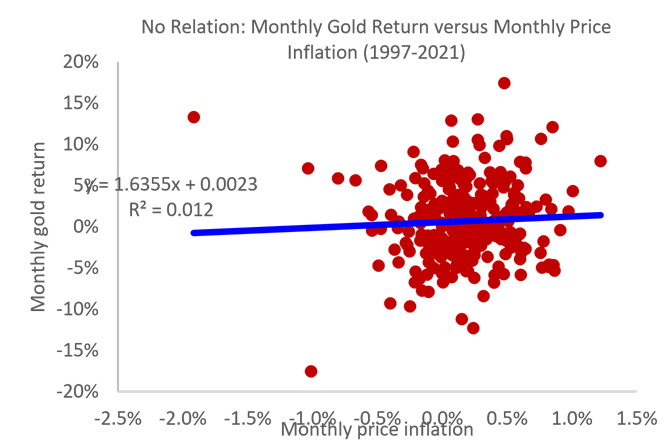

Our primary defence has been our commitment

to geographic, currency and asset diversification

(the only free lunch in investing). We have

complimented this position through our alpha

tilts, including being short credit, long Yen, long

volatility and the significant holding of gold – all of

which allowed us to provide positive returns

through the more challenging first quarter of 2025

– which we will expand upon shortly as we

circulate a note reflecting on the more turbulent

first quarter.

Our focus on capital preservation first has

allowed us to calmly navigate markets and we

have been able to sleep soundly through the

increased volatility. And hopefully so have you.